You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

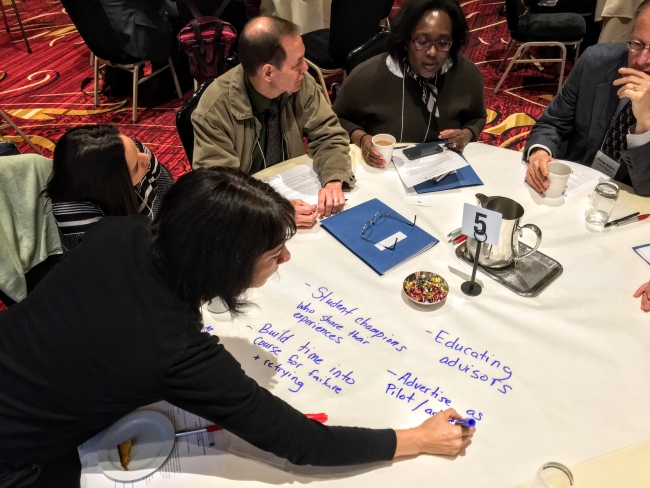

Conference goers discuss how to get students interested in online learning.

Carl Straumsheim

NEW YORK -- Administrators sometimes disagree with faculty members about the value of online education, and enthusiastic instructors sometimes clash with skeptics. But what can colleges do when their students are the ones resisting change?

The question emerged here last week as the Teagle Foundation, which supports liberal arts education, brought together grant recipients to provide updates on nine projects involving blended learning -- face-to-face courses with some online content. The collaborative projects, many of which won’t conclude until 2017 and 2018, have attracted participation from more than 110 faculty members and staffers and 115 students at about 40 colleges and universities in 16 states.

The goal of the projects, foundation president Judith R. Shapiro said in a letter to attendees, is to avoid “innovation fetishism” and devote time and effort to initiatives that -- while they may not promise to revolutionize liberal arts education -- could advance blended learning in meaningful and measurable ways.

More specifically, grant recipients were asked to consider three questions: Which learning strategies and technologies can lower costs, improve access to and the quality of education, and fit liberal arts curricula?

During the two-day conference, representatives of each project were invited to share some early successes and challenges, then collaboratively identify ways to tackle those challenges going forward. Amid issues such as picking a suitable technology platform, detailing intellectual property rights agreements and scheduling across time zones, several participants raised the issue of resistance -- not just from faculty members not participating in projects involving online education, but from their students.

During the two-day conference, representatives of each project were invited to share some early successes and challenges, then collaboratively identify ways to tackle those challenges going forward. Amid issues such as picking a suitable technology platform, detailing intellectual property rights agreements and scheduling across time zones, several participants raised the issue of resistance -- not just from faculty members not participating in projects involving online education, but from their students.

It's a twist on a conflict that usually plays out between proponents and opponents of any kind of online education. Students, meanwhile, are automatically viewed as “digital natives” happy to see their instructors embrace technology in their courses -- or so the assumption goes.

Six member institutions of the Council of Public Liberal Arts Colleges, who are collaborating on hybrid courses in the field of indigenous studies, said low enrollments stemming from student resistance is the “greatest challenge” facing their project so far.

“We knew that promoting online classes to students who had chosen a public liberal arts model would be a challenge; thus we are not that surprised by the often inconsistent enrollment in our classes,” the colleges wrote in a project update report. “However, enrollment has been a bit more uneven than we expected, even factoring in our audience, given that we have such high demand on our campuses for greater variety in the indigenous studies curricula on our campuses.”

The COPLAC project is typical of the grants awarded by Teagle. Most of them involve cross-institutional collaboration to create courses or modules meant to benefit students at a multiple institutions. About two-thirds of the colleges participating in this round of grants are liberal arts institutions.

Loni Bordoloi, one of the foundation’s program directors, said resistance from students came as a surprise both to the foundation and the grant recipients. “But I think it does make sense,” she said as she summarized the grant recipients’ early challenges. “Your students chose your institutions for a reason. They wanted, by and large, a residential liberal arts experience.”

As participants discussed ways to get students interested in blended learning, their answers tended to fall into two major categories: communication and normalization.

Several project members said they saw a need to alleviate student concerns that their grades won't suffer if they volunteer to experiment with blended learning. Potential solutions included starting hybrid courses off with low-stakes assignments, letting students evaluate the course halfway through the semester and recruiting former students to serve as hybrid learning “ambassadors.”

“Faculty members as well as communications people need to begin [communicating] in a systematic, institutional way,” said William Tyson, president of the media relations firm Morrison & Tyson Communications. “That takes the president, the chancellor saying -- and the faculty agreeing -- that this is core to the institution.”

In addition to a consistent communication strategy, participants said, colleges could consider creating a centralized hybrid learning office and perhaps even making hybrid courses a requirement for graduation -- administrative changes that position hybrid learning as a central part of a liberal arts education.

Rui Cao, instructor of Chinese at Schreiner University, was one of several participants who said faculty members need to be aware that blended learning may clash with student expectations. Instead of in a hierarchical model where faculty members lecture and students listen, the blended learning model challenges students to assume a more active role, she said, adding that there should be ample training opportunities both for faculty members and students.

“The reason that we see sometimes resistance both from our students and from faculty to this kind of learning is neither of us are fully prepared for this new era,” Cao said. “If both students and teachers are realizing this changing dynamic in our classrooms, that’s going to prepare us better.”